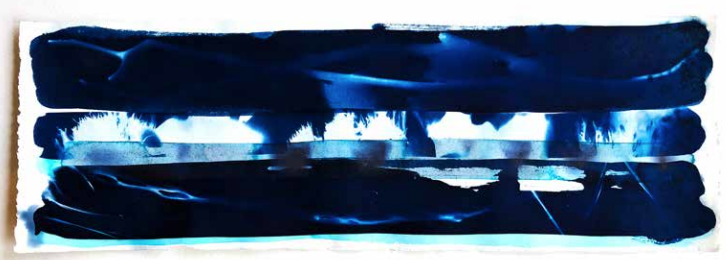

Photo: One of Daniela’s pieces from the series titled, “There is no time but the light remains.”

Daniela Naomi Molnar is a Portland artist, poet, writer, teacher, mentor, climate activist and a grandchild of Holocaust survivors. She began her creative journey as soon as she was old enough to hold a paintbrush. Her educational background is a unique blend of science and art; she received an undergraduate degree in environmental studies and a graduate degree in scientific illustration and worked with Scientific American Magazine for many years.

Several years ago, Daniela’s interest in scientific research and her art converged as she found herself drawn to the origins of colors. She often uses natural pigments in her work, and she became interested in the geology, biology, or botany backgrounds of specific colors.

When she started a residency in New Mexico in October 2020, she began creating paintings using the cyanotype process. “I was in the mountains of Northern New Mexico, and I was just completely smitten by the light,” says Daniela. “All I wanted to do was work with the light.”

Daniela working on a piece of art made using the cyanotype process in the studio during her residency at Mission Street Arts in Jemez Springs, NM. Photo courtesy Mission Street Arts.

Daniela uses a mixture of chemicals during the cyanotype process, which, when exposed to sunlight and washed in water, oxidize to create images. “You can combine them and paint with them under fluorescent light, and nothing will happen,” explains Daniela. “I’m painting the chemicals onto paper, and then I’m placing objects that I find on walks in the forest, the city, or sometimes objects that I’ve inherited from my grandparents onto the paper. Then I put the whole assemblage into the sun, and anywhere that the object is blocking (the light) is going to be white.” She can also manipulate some of the effects by spraying water or changing the pH with baking soda or salt.

The chemical reaction to the uncovered part of paper turns it into a vibrant blue that is known as Prussian blue. Prussian blue was the first modern synthetic pigment and the “blue” in blueprints.

Enjoying this new process, Daniela decided to research the origin behind Prussian blue. It turns out that intense blue pigment has a very complicated history.

The pigment was accidentally created around 1706 by a paint maker named Johann Jacob Diesbach, who was trying to make a red dye but accidentally mixed the wrong compounds together, making iron ferrocyanide, which had a very distinct blue hue.

Before this discovery, many painters and artists did not have access to a long-lasting blue pigment because their options made from lapis lazuli were costly. Then in 1752, the French chemist Pierre Macquer made the discovery that Prussian blue could be converted to iron oxide plus a volatile component and that these could be used to reconstitute it. The new component was what is now known as hydrogen cyanide or prussic acid.

Researching further, Daniela found out that prussic acid is also part of the chemical makeup of Zyklon B, the lethal gas used to kill prisoners in Auschwitz-Birkenau, Majdanek, and other Nazi death camps. “Zyklon” translates to “cyclone,” and the “B” stands for Blausäure, “blue acid.” Inside some of the death camp bunkers, you can still see traces of the same vibrant blue that characterizes cyanotypes on the walls.

It was then that Daniela realized the connection between the art she had been doing for years – visually presenting ideas about climate change – and her new cyanotype art and uncovering the history of Prussian blue as a 3G.

“I just went down this rabbit hole of climate grief, and doing this research – I was just like incredibly taken by the emotional impact of what I was discovering,” says Daniela. “I couldn’t compartmentalize it anymore. I just needed to experience that grief and process it through the paintings.”

Through creating the “Cyclone B” paintings, as she refers to them, she realized how grief could be creative fuel, and began to understand and cherish the duality of the color. “When you put Prussian blue onto a piece of paper or canvas, it’s instantly alive,” says Daniela. “Then there’s also this quality to it that’s deadly and murderous. That kind of complexity is very similar to the complexity that grief often takes in our lives – of being both hardship and struggle and also love and gratitude. All of those things combined.

“My grandmothers survived Auschwitz. My grandfathers survived labor camps,” continues Daniela. “These paintings are a record of ongoing intergenerational trauma and grief. They are also tokens of transformation, records of attempts to shift that trauma.”

Since returning to Portland from New Mexico, she has continued working on the series but realized that the light is calmer and more diffused at home, changing the way that the paper gets exposed. So she’s currently applying for more residencies in the desert Southwest to “reinvigorate the series.”

She has sold a few pieces through people contacting her directly, but since she is not finished with the series, she has not lined up a formal show but has been sharing her cyanotypes informally through Instagram.

“The reaction that people have to them is really interesting,” says Daniela. “I intentionally make the work very beautiful. I think beauty is a potent tool for drawing people into these ideas that are challenging. People are typically just enamored by the color and then there’s this sort of double take when they realize the complexity of what they’re looking at. It’s a real opening to conversation that I’ve appreciated.”

To see more of Daniela’s work, visit danielamolnar.com.