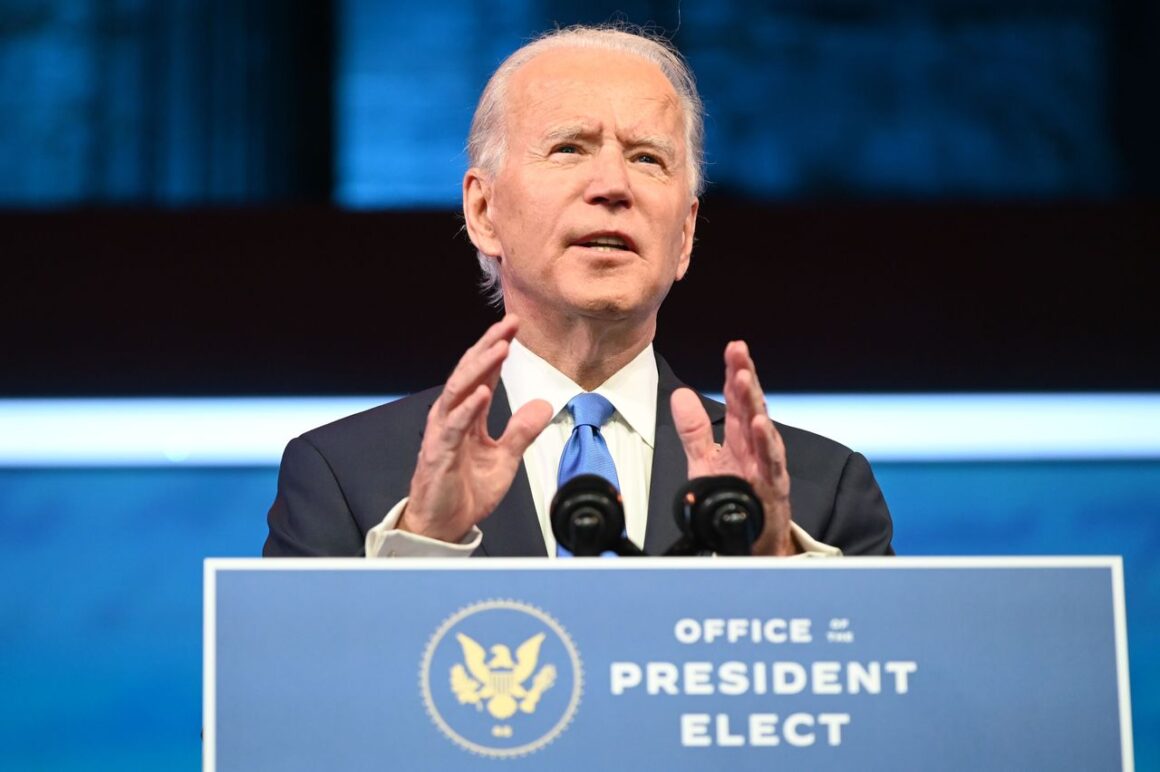

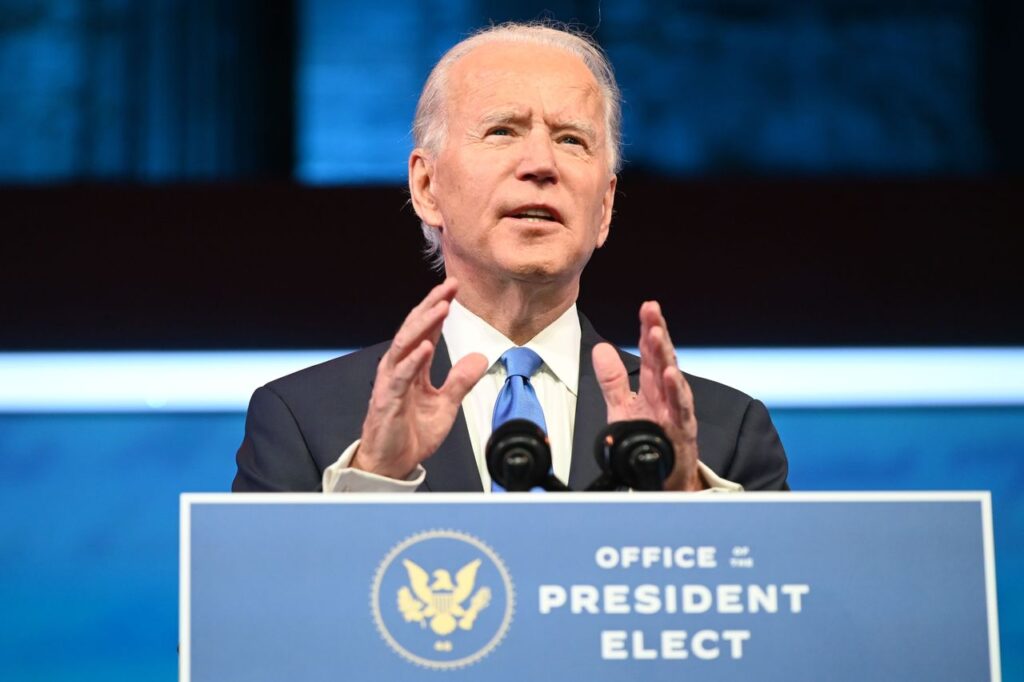

Photo: U.S. President-elect Joe Biden, pictured here on Dec. 14 as he delivers remarks on the Electoral College certification in Wilmington, Delaware. (Roberto Schmidt/AFP/Getty Images/TNS)

By Kerry Tymchuk

During the nearly 25 years I served as an aide to a Congressional representative, a cabinet secretary, and two U.S. senators, I was privileged to have a bird’s eye view of how politics is played and policy is made at the highest levels of American government. One of the most fascinating aspects of this view was the opportunity to observe and take stock of the character and qualities of our nation’s elected leaders–one of those being the man who on Wednesday will become the 46th president of the United States.

I was working for Sen. Bob Dole of Kansas in 1994 and served as his representative at meetings where then-Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Joe Biden and the ranking Republican, Strom Thurmond were attempting to reach consensus on a criminal justice legislative package. At 91 years old, Thurmond was very hard of hearing, occasionally confused, and heavily dependent on staff–all of which caused the meetings to drag on. I expressed concerns to Dole that Thurmond’s condition might prevent any agreement. Dole assured me that Biden was precisely the right senator to handle the situation. He was correct. Rather than trying to take advantage of or becoming frustrated with Thurmond, I watched as time and again Biden would halt the proceedings to make sure that Thurmond understood the impacts of every change that was being made to the bill.

Biden’s inherent decency and empathy were again on display in fall 2003, when I was working for Sen. Gordon Smith. The tragic suicide of Gordon’s son, Garrett, after years of battling mental health issues, led the senator to consider resigning his seat. Senators of both parties offered shoulders for Gordon and his wife, Sharon, to lean on. One colleague, however, reached out more often and more meaningfully than any other. In his book, “Remembering Garrett: One Family’s Battle with a Child’s Depression,” Gordon wrote “Joe Biden also proved a real brother. On three occasions he pulled me down into a Senate chair next to him to counsel me about grief. He knew the subject intimately, as his wife and his daughter had been taken from him in a traffic accident just weeks after his first election to the Senate in 1972.”

Biden would suffer another tragedy when brain cancer claimed his son, Beau, in 2015. Like Gordon, he would turn his grief into a book, “Promise Me, Dad,” which brought him to Portland in 2017 for a speech at the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall. Biden’s schedule included a meeting with Antoinette Hatfield, the widow of Mark Hatfield, who had served in the Senate with Biden for 24 years. Mrs. Hatfield asked me to accompany her to the meeting in the backstage “green room” of the Schnitz.

We were instructed by the event sponsors to be there at 7 p.m. and to expect a very brief greeting as Biden would need some down time before the 7:30 p.m. program began. We arrived on time to an effusive greeting from Biden. Despite our offering to excuse ourselves, and despite the event staff came into the room to hint it was time we left, Biden kept the conversation going right up to and beyond 7:30. He was unfailingly kind and gracious to Mrs. Hatfield, and shared memories of his admiration of and friendship with her husband.

When I mentioned that my son, Clark, was an admirer of his, and that, like me, was hoping he hadn’t ruled out a 2020 presidential run, Biden immediately pointed to my cell phone and insisted I call Clark, who was attending Oregon State University, so he could talk with him. I listened with tears in my eyes as the two had a conversation about college classes and intramural football, and as Biden encouraged Clark to make a positive difference in his eventual career.

Read the entire article here.

Kerry Tymchuk became executive director of the Oregon Historical Society in 2011 after a long career in politics. He lives in Beaverton.