By Ellen Rifkin

In an Israeli children’s story, a Bedouin girl sits tall on her camel, leading her community to an oasis during Ramadan. Her grandfather, their former leader, has just died; when the mourning period concludes, his “she-camel” kneels before Fatima, indicating her destiny. Fatima is prepared. Riding alongside her grandfather during this fasting period, she has learned to orient to the stars and experience the faith needed to follow their beckoning. Under the night sky and her grandfather’s tutelage, she has learned that a pure heart lets in light and understanding.

“In Fatima’s Footsteps” is part of a bilingual Hebrew and Arabic anthology entitled Sweet Tea with Mint, published in 2016. It includes three stories originally written in Arabic and three in Hebrew, each framing a major Jewish, Muslim or Christian holiday. The book was created by the Hagar Association: Jewish-Arab Education for Equality, a bilingual, bicultural school in Israel’s south that honors the histories and cultures of both Jewish and Arab children. Like Fatima and her grandfather, Hagar’s visionary teachers and families trust in the power of the heart: their own fixed star is a vision of a shared society.

I met these inspired educators while volunteering in Hagar’s afterschool program last spring. Though not formally associated with the Hand in Hand schools (cofounded by Portland’s Lee Gordon in 1997), Hagar (founded in 2006) shares with them its mission of bridging the chasm between Jewish and Arab communities. My congregation, Eugene’s Temple Beth Israel, forged connections with Hand in Hand’s Jerusalem school through Rabbi Yitzhak Husbands-Hankin. While traveling in Israel, I wanted to experience the Negev as well as learn about Israel’s bilingual schools, and thus I gravitated to Hagar in Beersheva. I also visited Neve Shalom, the Jewish-Palestinian community and school (founded in 1979) that mentored the first teachers at both Hagar and Hand in Hand.

Observers say Hagar’s success is “almost a miracle” in conservative Beersheva, where religious Jews share little more than sidewalks with Christian and Muslim Arabs, whose relatives may live in Gaza or Hebron. Russian and Ethiopian Jews, and Bedouins with their own stories of displacement, add to the challenges of co-existence in the Negev. Hagar weaves these strands into a tapestry through its “Roots” curriculum, guiding students to discover their unique family stories and community/national identities and then to share these stories through multimedia projects. Though counterintuitive in the Middle East context, this belief that solid grounding in your own narrative allows empathy for your friend’s is validated by the school’s success. Hagar’s academic excellence and inclusive culture continues to draw families from all sectors.

As a central part of Hagar’s program, Sweet Tea with Mint honors the role of religion in its students’ cultures and unearths commonalities among the faiths. At one point in the Ramadan story, Fatima’s grandfather admonishes sword fighters that without practicing mercy, their fasting is meaningless. In the Yom Kippur story “Silent Language,” Wise Sallah urges his fellow Jews to extend compassion to Na’im, a mute boy painfully finding his way to atonement. Hagar’s teachers help students explore how forgiveness, faith and charity are core values their traditions share.

As a central part of Hagar’s program, Sweet Tea with Mint honors the role of religion in its students’ cultures and unearths commonalities among the faiths. At one point in the Ramadan story, Fatima’s grandfather admonishes sword fighters that without practicing mercy, their fasting is meaningless. In the Yom Kippur story “Silent Language,” Wise Sallah urges his fellow Jews to extend compassion to Na’im, a mute boy painfully finding his way to atonement. Hagar’s teachers help students explore how forgiveness, faith and charity are core values their traditions share.

The anthology’s creators deliberately chose settings through which Jewish and Arab children learn that their worlds haven’t always been separate. “Silent Language” takes place in pre-Mandate Tiberias, where Jewish and Arab fishmongers, date sellers and cafe owners break down the market together in anticipation of Kol Nidre, and as one community contributes food to Avram the coalman after a stunning robbery. In the title story, Grandmother Yakut longingly recalls her family’s annual Mimouna feast with Muslim neighbors in Morocco, a joyous end-of-Passover tradition. The loss of a time when Jews and Arabs lived among each other and made peace after quarreling is a palpable ache to her.

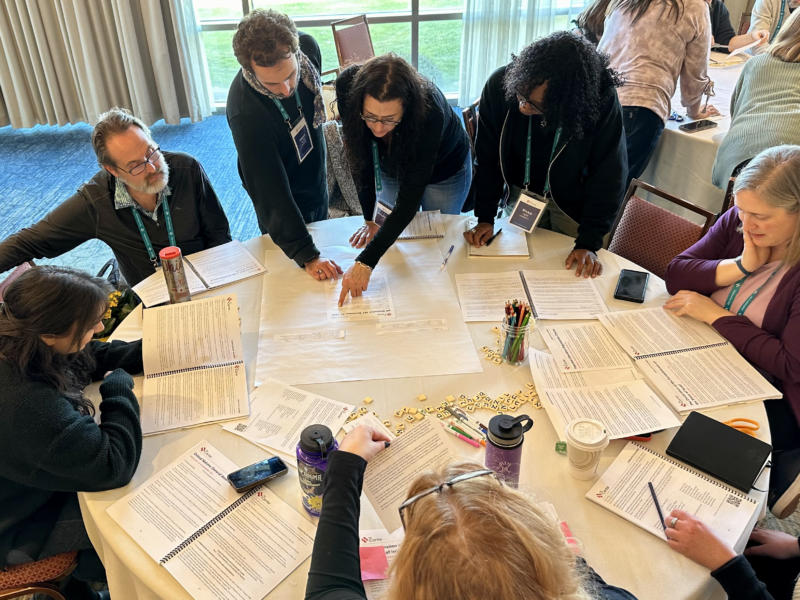

Hagar students learn actively and collaboratively. After researching the history of Mimouna in Arab countries, they incorporated the celebration into the school’s Passover tradition. Emulating Hajj Qassim in “The Hidden Helping Hand” and the merchant Mimoun in “Sweet Tea,” older students worked with preschoolers, assessing their project through Maimonides’ levels of charity and Koranic teachings.

To create the anthology, Hagar staff joined with education faculty at Beersheva’s Ben Gurion University and collaborated with distinguished children’s writers in Hebrew (Ronit Chacham) and Arabic (Hadeel Nashif, Al-Tayeb Ghanayem and Sheikha Hussain Haliwa). In the book’s painstaking development, certain elements were intentional – illuminating common spiritual values and highlighting settings where a “shared society” once existed. Serendipitously, female protagonists emerged in more than half the stories.

The tales are complex and radiant. While including rare, honest portrayals of impoverished communities on Israel’s “periphery,” their deeper focus is on the heart: children’s yearning to understand and belong.

At integrated Hagar, as well as in six traditional Jewish or Arab schools where the Sweet Tea curriculum has been implemented, students delightedly recognize themselves in the characters’ struggles. Evaluators observed that young Jewish students identify with Fatima’s little brother, who wants desperately to fast for Ramadan but can’t quite pull it off. Responding to the Shavuot story, which highlights fears of deportation among African immigrants, big sisters of all backgrounds recognize and identify with the older sib encouraging her little sister’s bravery.

Kibbutzim College now uses the anthology in its teacher training program. Israel’s Ministry of Education recently authorized the use of Sweet Tea nationally – but doesn’t provide funding. Hagar faces an uphill battle underwriting the teacher trainings necessary to introduce Sweet Tea into mainstream schools, which are overwhelmingly unfamiliar with multicultural curricula.

The fears and prejudices of Jews and Arabs toward each other are reflected and perpetuated in Israel’s largely segregated educational system. In urban schools where Arab kids comprise part of the student body, their histories and holidays are invisible.

Two years after its founding, when students returned to Hagar after Operation Cast Lead and the rain of missiles on Beersheva, teachers observed with near despair a new, ugly “othering” in their behavior, learned from relatives during their evacuation to the north. Staff learned then the lesson that sustains them through cycles of violence: if they keep faith with the school’s vision, students reorient also.

Israel’s bilingual, bicultural schools break down walls of silence and fear. Hagar’s Sweet Tea with Mint uses the magic of story to conjure the plausibility of a shared society and shines a light on a shared spiritual foundation. As the school offers this groundbreaking curriculum to Israel’s mainstream, its fate is worth our attention.

Ellen Rifkin, a resident of Eugene, visited schools in Israel and the West Bank during spring 2018.