On Manhattan’s Upper West Side, Missy Sokolsky is rehearsing “Fiddler on the Roof.” Missy’s third-grade class is staging the play because lyricist Sheldon Harnick’s son Matthew is one of Missy’s classmates at the elite Columbia Grammar and Preparatory School. The year is 1978 and 9-year-old Missy is playing Yente. She is a fourth-generation native New York Jew, rooted at the center of a vibrant, affluent family and community. The Sokolskys are Reform, and not particularly observant, but this is a city permeated with a strong Jewish culture. Being Jewish is a vital part of Missy Sokolsky’s burgeoning identity.

In a low-income neighborhood of San Diego, Melissa Hart and her mother are moving up in the world: from a shared cot in a shelter to a rented room in a stranger’s home. They will be sharing a bunk bed newly purchased from Goodwill with scraped together dollars. The year is 1979 and the mother-daughter duo is all alone in the world. Ten-year-old Melissa is essentially raising herself, doing her best to also nurture her fragile, emotionally exhausted mother. Melissa Hart has no encounters with Jewish people.

From the darkened interior of a small movie theater in Portland this past summer, Southwest Washington resident Liss Haviv watches the screening of Ken Klein’s film “Wandering in the Woods” with ferocious interest. The filmmaker’s quest to uncover what it means to be Jewish strikes a particular chord for the 45-year-old Haviv as she struggles to reconcile Missy Sokolsky and Melissa Hart into one merged identity – hers.

Haviv was born Missy Sokolsky. At age 10 she became the victim of a crime known as family abduction, which ripped her from Judaism and turned her into Melissa Hart.

Haviv’s mother used a stolen, forged baptism certificate to obtain new identification documents and begin life under a new identity so that the ex-husband she despised – Missy’s father – could no longer be part of their lives. This also eliminated everyone else Missy had ever known and loved. Haviv says, “It was like entering the witness protection program – in a day, I was severed from everything and everyone that made up my universe; everything that makes up identity, even my own name. I literally became someone else, overnight. I was ordered to lie about who I was and where I was from.”

In her early 30s Haviv made two startling discoveries. First, she discovered that what had happened to her was a crime with a name and hundreds of thousands of fellow victims. “It had never occurred to me that there might be others,” she says. “When on rare occasions I disclosed that I started fifth grade living under an alias, on the run from the FBI, I didn’t ever expect anyone to say ‘oh yeah, me too.’ ” Yet in 2001 she discovered that children abducted by family members account for the overwhelming majority of all cases of child abduction in America. “I learned that when places like the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC) and the Polly Klaas Foundation deal with cases of child abduction, nearly 80% of the time they are dealing with cases like mine. I always thought places like that were reserved for kids like Elizabeth Smart. I was wrong. Being hidden by a parent didn’t make me any less ‘missing.’ Or safe. Parents who abduct are parents at the end of their rope. My mother seriously considered killing herself and taking me out with her.”

Discovering she was not alone in her unusual childhood experiences was a pivotal life moment for Haviv. “Learning that what my mother did is a felony and considered a form of child abuse completely reframed how I viewed her, my childhood, my adult struggles, everything.” She turned to the NCMEC for help, and that’s when the second surprise came. “I found that although missing child agencies do an excellent job locating missing children and supporting victims’ families while they search, cases are considered closed the moment a missing child is located.” Haviv learned this was true not just for family abduction, but for all kinds of child abduction cases. She observes, “The trauma of abduction does not disappear the day a missing child is found; but no one was going beyond recovering missing children, into helping missing children recover.”

Haviv further noticed that the research on child abduction was lacking data and testimony from one very important source: the abducted. Data were coming from victims’ parents rather than from the victims themselves. As a Fulbright Scholar in cultural anthropology, she grasped the detriments of this approach and set out on a quest to improve America’s missing child response by “adding the voice of the abducted to the public and policy discussions on child abduction.”

With assistance from NCMEC and a grant from the U.S. Department of Justice, Haviv opened a nonprofit called Take Root in 2003. The agency, headquartered in Southwest Washington, established the first and only peer support program for victims of child abduction after they are found. Take Root’s groundbreaking work with victims has built an unparalleled knowledge and database, which the agency’s Child Abduction Studies Program distills into advocacy initiatives, professional training and public education.

After a decade at the helm as executive director, Haviv has become the nation’s leading expert on the victimology of child abduction. Her work and insights are used by entities ranging from the U.S. State Department to law enforcement agencies coast to coast. Industry colleagues such as Wendy Jolley-Kabi, executive director of The Association of Missing & Exploited Children’s Organizations, and Robert DeLeo, executive director of the Polly Klaas Foundation, respectively use words like “game-changing” and “paramount” to describe Haviv’s substantial contribution to the field of missing child services.

Although she has an incredible story, a piece of the puzzle was still missing for Liss Haviv. “I do a lot of media interviews,” she says, “and reporters sometimes ask why I was able to go on and start Take Root and create something from the ashes when so many other victims are shattered by the trauma. I never had a good answer.” She has one now, and she found it the first time she walked back into a synagogue, 34 years after being abducted away from Judaism. This happened just last year, at Vancouver’s newly erected Kol Ami. Haviv immediately burst into tears. “All kinds of dots suddenly connected,” she says. “It was like being hit by a ton of bricks.”

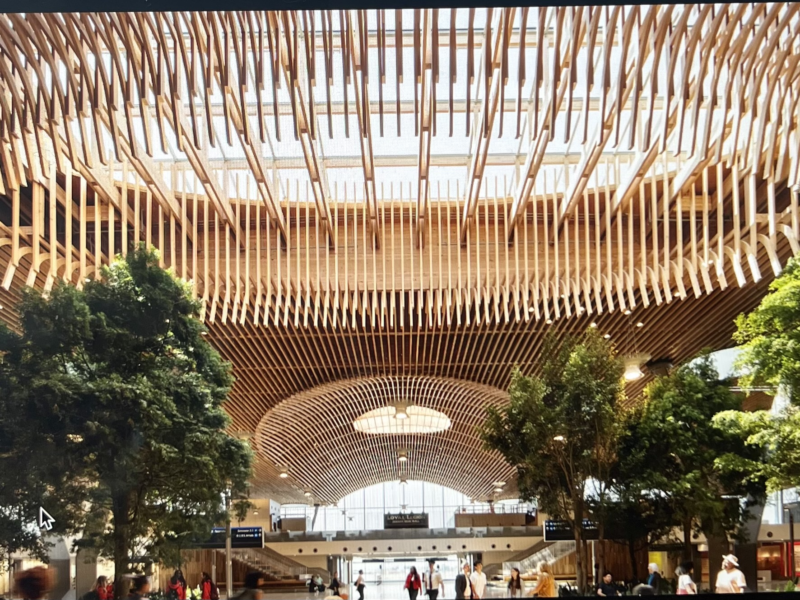

Haviv will share the realization that hit her and the role Judaism has played in her story when she speaks at Kol Ami on Nov. 3 as part of a fundraising event for Take Root. Despite frequent public speaking about abduction, she does not often share her personal story, so this will be a special night. Joining in that spirit will be her husband, classically trained Israeli guitarist Avi Haviv, who began his professional career at the age of 14 accompanying Miri Aloni. After a lifetime of traveling the world as a musician, he has settled into playing jazz and classic rock at venues and events throughout Portland and Southwest Washington. The Nov. 3 fundraiser will be a rare concert of his original music. It’s a great opportunity to visit Kol Ami’s lovely new synagogue, to support a worthy cause and to hear Haviv’s inspiring message about what rediscovering Judaism has taught her.

AVI TAKES ROOT

An evening of original music by Avi Haviv, in support of Take Root, Sunday, Nov. 3

Kol Ami, 7800 NE 119th St., Vancouver, WA 98662

Tickets: $36

Join us at 5:30 for a hosted wine hour with tours of Kol Ami and

a gallery showing of artistic and literary works by former missing children. The 90-minute concert will begin at 6:30.

Purchase tickets online at takeroot.org/concert or call 800-ROOT-ORG.