After decades of doing business in China, Michael Bloom thinks being Jewish there is an asset. “When the people who work for me in China say their boss is Jewish, I gain a few stages in recognition,” he says. “There are bestsellers like How to Become a Jewish Businessman. They think Jews are smart and good at business.”

His upcoming talk, “Community Without Walls: Jews, Business and China,” will feature Michael’s insight, experience and wonderful stories. The free May 14 event is co-sponsored by the Jewish Federation of Greater Portland and the Mittleman Jewish Community Center. As a Community Without Walls program, it will meet downtown at the Northwest Health Foundation Conference Center.

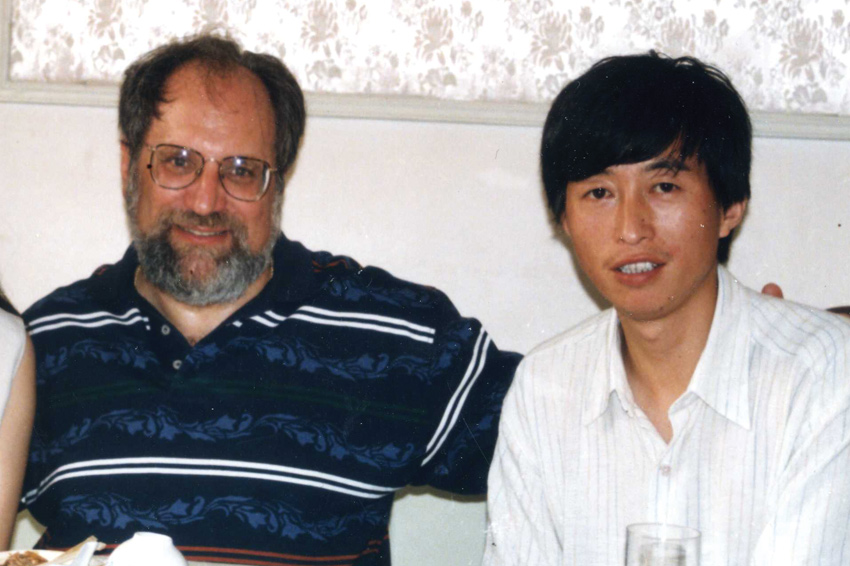

Portlander Michael Bloom is president of Sinotech, a company that manufactures custom-engineered products in China for mostly American manufacturers. Customers come to Michael with engineering drawings, and he takes it from there. Employees at Sinotech’s three locations in China locate and negotiate with Chinese factories, which then build the product.

When asked how his business started, Michael points to serendipity, not intention. An electrical engineer by training, he grew up in the Bronx and still speaks only a few polite Mandarin phrases. It started in 1983, only 11 years after President Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit to China began normalizing the relationship with the United States.

“While living in New York, I was exhibiting at a trade show in San Francisco and met a Chinese man, who was being ignored because of his language skills,” Michael says. “I knew he was staying at the Chinese consulate in Manhattan. I said ‘Why don’t we meet?’ He said he’d be with a delegation from China, and I told him to bring them along. I set up a day that included visits to Brookhaven National Laboratory, companies that I designed products for and LaGuardia Community College, where I taught. That day the delegation experienced their first kosher meal – at my place.

“In those days, the relationship between the countries was tenuous, so the Chinese Vice Consul came along to keep his eye on everyone,” Michael says. “When we became friends, the Chinese government asked if I could set up an internship program for Chinese scientists and engineers. I was the coordinator of cooperative education at LaGuardia Community College, and my job was to set up internships for college students.”

Michael was delighted to work with students from China. He didn’t know it would soon lead to a new career.

Michael says that while looking for an internship, he met staff from a New York company who wanted to connect with a company in China to make certain parts. “A light went off – wait a second, this sounds like a business!” Michael chose one of his best student interns to set things up when the student returned to China. That intern, Frank Luan, and Michael still work together and remain close friends.

Meanwhile, Michael and his wife, Jaime, wanted to leave New York. They moved to Portland in 1989 and today live in the Raleigh Hills neighborhood. They have four grown children, two grandsons and three Havanese dogs, which Jaime breeds and shows. One daughter, Melissa Bloom, is the executive director at Shaarie Torah and daughter Liza Milliner is on the board at Congregation Neveh Shalom. Daughter Jeramie spent a few years in Israel and in Shanghai, and son Scott is vice president of engineering at a Silicon Valley high-tech firm.

Michael and Jaime belong to multiple synagogues, and Michael has served on the Congregation Kesser Israel board. He also serves as a guest lecturer on The American Entrepreneur in China at the University of Portland and is an advisor to the Portland State University International Management master’s program. He is a board member and past president of the Northwest China Council – a group of 300 mostly Oregonians interested in Chinese business, language, culture and current events.

Michael looks forward to his May 14 talk and is trying to select topics the audience will enjoy. Having visited China at least 100 times, there is much to choose from. He might talk about the exotic foods he’s tried like camel hump, cicada cocoon and poisonous snake, or experiences like Shanghai tours that focus on Jewish refugees during World War II. He can talk about everything from kosher meals with Chabad to the time he was stranded on a sandbar.

“We chartered a Chinese fishing vessel in Bohai Bay, which separates China from North Korea,” he says. “We got stuck in a sandbar with Chinese fisherman for 10 hours. They asked, ‘Why do Americans have guns?’ and ‘Why don’t Americans like black people?’ It was amazing how much they knew about the West compared to what we know about China. They knew our weak spots.”

Three cultural concepts are key for Americans doing business in China, Michael says. First is the importance of saving face or not humiliating anyone. “In doing business, if something goes wrong an American might yell at the factory owner,” Michael says. “In China you must establish a partnership and not yell at the guy.”

Some people say the second concept, guanxi, means bribery, but Michael sees this differently. “It means to build a relationship,” he says. “You do mutual favors for each other without the expectation of a specific benefit. It means, ‘We’re friends, we’re partners, and someday we’ll be there for each other.’ American businessmen depend on contractual, written laws. If someone violates a contract we sue them. In China, it’s relationship based. If we get a shipment of bad parts, it may be clear that the factory is at fault, but we try to reduce our losses and the factory’s losses, as well.

“One of the biggest problems is most people have misimpressions about China,” Michael says. “I hope they come away from my talk with an appreciation of what it’s like. You can’t understand China without understanding the historic exploitation of the country and the impact the Cultural Revolution had on individuals. Today, we’re becoming polarized and see China as our enemy. They are our competitor, but so far they are not our enemy. It depends on what they do, but it also depends on what we do.”