In the first weeks of World War I, Jews throughout the world prepared to celebrate the New Year of 5675 with fervent prayers for peace and the safety of Jews in Europe.

The war would embroil countries that were home to more than four million Jews, and life for them – and the world order – would be changed forever. “The war was a total war and it was therefore a total disaster to all concerned,” notes Rabbi Berel Wein, a popular lecturer on Jewish history. Although the United States did not enter the war until 1917, American Jews raised money to aid beleaguered Jewish communities, and, when the time came, signed up to serve.

On Aug. 27, 1914, The Oregonian reported that a national Jewish organization was calling on congregations to insert a prayer for peace into their services “during the war.”

Soon after, Rabbi Jonah Wise of Portland’s Congregation Beth Israel, the city’s most prominent Jewish congregation, spoke to more than 100 people gathered at a current events class at First Presbyterian Church. “The treatment of the Jew after this war,” he predicted, “will be the barometer of civilization by which we may judge the condition that will confront the masses of Europe.”

Although an outspoken pacifist from the outbreak of the war until the United States entered it, Wise soon joined with Ben Selling and other community leaders to raise money for the “miserably poor” Jews of Europe in cooperation with a new national group, the Joint Distribution Committee. By November of 1915, Portland Jews pledged to raise at least $20,000 toward the relief effort.

“One million five hundred thousand Jews are actually starving in Europe today,” Selling told The Oregonian. “Jewish men are in every army involved in the war. Their homes and families are in every country of Europe, and the relief work is to be extended to all.”

Within a month, more than $16,000 had been pledged – and Portland’s goal was raised to $25,000. Selling, Portland’s premier philanthropist, made a personal commitment of $100 a month for a year, while others pledged what they could, some just $1 a month.

Among the more unusual contributions was a $1 bill mailed in by the warden of the Oregon State Penitentiary on behalf of an inmate who, The Oregonian said, wanted to donate his tobacco and “canteen” money to the relief effort.

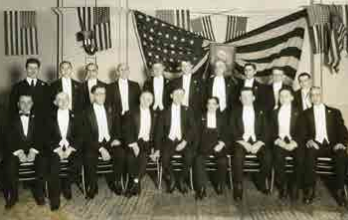

After President Woodrow Wilson declared Jan. 27, 1916, as a day “on which the people of the United States may make such contributions as they feel disposed for the aid of the stricken Jewish people,” Wise and others organized a committee of leading citizens, with names like Corbett, Olmstead and Ainsworth. Oregon Gov. James Withycombe promised to issue a proclamation similar to the president’s.

Wise said the Jewish community preferred to take care of its own, but “the burden is becoming too heavy for us. Of all the Jews in the world,” he continued, “four-fifths are in the warring armies or staggering out of their paths.”

People throughout the city, Jews and non-Jews, stepped up. One report noted that six “working girls” pooled money from “their meager pay envelopes” to send in a money order for $5. “The most touching donation,” The Oregonian said, came from a “down-and-outer” who had only 25 cents to his name. He paid 15 cents for lodging and breakfast, then gave one of his two remaining nickels for Jewish relief. “If I had more,” he said, “it would be a 50-50 split just the same.”

The public library ran notices of new books about Jewish history and life, noting that the relief effort made Portlanders want to know more about Jews and Judaism. In the spring of 1916, the Portland Newsboys’ Association put on a vaudeville benefit at Neighborhood House for Jewish war relief, featuring a talk by I.E. Tonkon, musical numbers and even a piano solo.

The Council of Jewish Women and South Portland Jews pitched in, working with the Red Cross and other organizations. In an unpublished 1982 history of Neighborhood House, Michele Glazer notes that in 1917 South Portlanders gathered to roll bandages and knit socks for the men overseas. In 1918 two Council members attended a series of “War Cookery” lessons and planned to share what they had learned with Red Cross workers.

Once America was in the war, Oregon Jews joined the 250,000 Jews throughout the country who served as soldiers. At one sendoff for 25 draftees, Wise and Alexander Bernstein, a Portland attorney, were the featured speakers at the party organized by B’nai B’rith lodges and the Jewish Welfare Board.

This was the first time Jews had fought in the American armed services in any numbers – constituting about 5% of the soldiers although only 3.3% of the nation’s population. About 3,500 were killed in action or died of wounds; another 12,000 were injured.

Wise himself sought to join the U.S. Army as a chaplain – and had secured the support of Beth Israel’s Board of Trustees in October 1918 – but the war ended on Nov. 11, 1918.

The Forward, in an article published earlier this year, described World War I as “a defining moment that changed American Jewish identity, power and values.”

The war’s most significant legacy, the article continued, “was to unite disparate strands of the American Jewish community – Germans, Eastern Europeans, Orthodox, Reform and socialists – around the single issue of helping their brethren in war-torn Europe and in Palestine” and noted that the war gave birth to the idea of an American Jewish community “centered on philanthropy.”

At the same time, the war created massive upheavals in Europe – upheavals that eventually led to World War II and the Holocaust. But even in the upheavals, there were seeds of hope.

The war also led to the crumbling of the Ottoman Empire – and to Britain’s issuance of the Balfour Declaration of 1917, confirming support for the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. A hope and a dream that would be realized a generation later, and only after another terrible war.

Sura Rubenstein is a Portland writer.